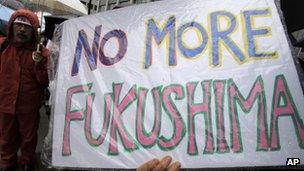

A Japanese parliamentary panel has delivered a damning verdict after investigating the accident at the Fukushima nuclear plant which followed an earthquake and tsunami on 11 March 2011.

Although such an event should have been predicted and planned for, the panel said, it found gaping holes in safety standards and emergency procedures.

Here is an outline of key quotes, findings and recommendations from the 88-page executive summary of the Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission’s report.

Disaster ‘manmade’ – chairman’s message

The earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011 were natural disasters of a magnitude that shocked the entire world. Although triggered by these cataclysmic events, the subsequent accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant cannot be regarded as a natural disaster. It was a profoundly manmade disaster – that could and should have been foreseen and prevented…

Our report catalogues a multitude of errors and wilful negligence that left the Fukushima plant unprepared for the events of March 11. And it examines serious deficiencies in the response to the accident by Tepco, regulators and the government.

For all the extensive detail it provides, what this report cannot fully convey – especially to a global audience – is the mindset that supported the negligence behind this disaster. What must be admitted – very painfully – is that this was a disaster “Made in Japan.”

Its fundamental causes are to be found in the ingrained conventions of Japanese culture: our reflexive obedience; our reluctance to question authority; our devotion to ‘sticking with the program’; our groupism; and our insularity.

(Chairman Kiyoshi Kurokawa)

Key findings

Collusion and lack of governance

The Tepco Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant accident was the result of collusion between the government, the regulators and [private plant operator] Tepco, and the lack of governance by said parties. They effectively betrayed the nation’s right to be safe from nuclear accidents. Therefore, we conclude that the accident was clearly “manmade”…

We believe that the root causes were the organizational and regulatory systems… rather than issues relating to the competency of any specific individual.

[All parties] failed to correctly develop the most basic safety requirements – such as assessing the probability of damage, preparing for containing collateral damage from such a disaster, and developing evacuation plans for the public in the case of a serious radiation release.

Organisational problems within Tepco

Had there been a higher level of knowledge, training, and equipment inspection related to severe accidents, and had there been specific instructions given to the on-site workers concerning the state of emergency within the necessary time frame, a more effective accident response would have been possible… Sections in the diagrams of the severe accident instruction manual were missing.

Emergency response issues

The government, the regulators, Tepco management, and the Kantei [prime minister’s office] lacked the preparation and the mindset to efficiently operate an emergency response to an accident of this scope. None, therefore, were effective in preventing or limiting the consequential damage.

In the critical period just after the accident, the Kantei did not promptly declare a state of emergency. The regional nuclear emergency response team was meant to be the contact between the Kantei and the operator, responsible for keeping the Kantei informed about the situation on the ground. Instead, the Kantei contacted Tepco headquarters and the Fukushima site directly, and disrupted the planned chain of command.

Evacuation issues

The Commission concludes that the residents’ confusion over the evacuation stemmed from the regulators’ negligence and failure over the years to implement adequate measures against a nuclear disaster, as well as a lack of action by previous governments and regulators focused on crisis management. The crisis management system that existed for the Kantei and the regulators should protect the health and safety of the public, but it failed in this function.

The central government… failed to convey the severity of the accident… [O]nly 20% of the residents of the town hosting the plant knew about the accident when evacuation from the 3km zone was ordered at 21:23 on the evening of March 11.

There was great confusion over the evacuation, caused by prolonged shelter-in-place orders and voluntary evacuation orders. Some residents were evacuated to high dosage areas because radiation monitoring information was not provided.

Continuing public health and welfare issues

[R]esidents in the affected area are still struggling from the effects of the accident. They continue to face grave concerns, including the health effects of radiation exposure, displacement, the dissolution of families, disruption of their lives and lifestyles and the contamination of vast areas of the environment. …

The Commission concludes that the government and the regulators are not fully committed to protecting public health and safety; that they have not acted to protect the health of the residents and to restore their welfare.

Approximately 150,000 people were evacuated in response to the accident… Insufficient evacuation planning led to many residents receiving unnecessary radiation exposure. Others were forced to move multiple times, resulting in increased stress and health risks – including deaths among seriously ill patients.

“If there had been even a word about a nuclear power plant when the evacuation was ordered, we could have reacted reasonably, taken our valuables with us or locked up the house before we had left. We had to run with nothing but the clothes we were wearing. It is such a disappointment every time we are briefly allowed to return home only to find out that we have been robbed again.” (Comment by a resident of Okuma, from report appendices)

Regulator failures

The regulators did not monitor or supervise nuclear safety… They avoided their direct responsibilities by letting operators apply regulations on a voluntary basis. Their independence from the political arena, the ministries promoting nuclear energy, and the operators was a mockery. They were incapable, and lacked the expertise and the commitment to assure the safety of nuclear power.

Operator failures

Tepco did not fulfil its responsibilities as a private corporation, instead obeying and relying upon the government bureaucracy of Meti, the government agency driving nuclear policy. At the same time… it manipulated the cosy relationship with the regulators to take the teeth out of regulations.

Shortcomings in laws and regulations

Laws and regulations related to nuclear energy have only been revised as stopgap measures, based on actual accidents. They have not been seriously and comprehensively reviewed in line with the accident response and safeguarding measures of an international standard. As a result, predictable risks have not been addressed.

The existing regulations primarily are biased toward the promotion of a nuclear energy policy, and not to public safety, health and welfare. The unambiguous responsibility that operators should bear for a nuclear disaster was not specified. There was also no clear guidance about the responsibilities of the related parties in the case of an emergency.

No ‘cosmetic solutions’

Replacing people or changing the names of institutions will not solve the problems. Unless these root causes are resolved, preventive measures against future similar accidents will never be complete…

The underlying issue is the social structure that results in “regulatory capture,” and the organisational, institutional, and legal framework that allows individuals to justify their own actions, hide them when inconvenient, and leave no records in order to avoid responsibility.

Sourced from BBC News