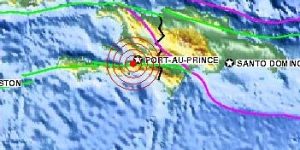

The green line south of Port-au-Prince shows the fault line where the 7.0-magnitude quake was centred. The epicentre was 10 kilometres beneath the surface. (U.S. Geological Survey)

Tuesday’s earthquake in Haiti was especially destructive because its epicentre was close to a major city and its hypocentre, or focal point, was close to the Earth’s surface, says a Canadian seismologist familiar with the area.

Natural Resources Canada seismologist John Cassidy says the 7.0 quake — centred just 15 kilometres southwest of the capital of Port-au-Prince — happened roughly 10 kilometres below ground.

“If the earthquake had happened further below, it would have lost its energy as it moved up,” he says.

When Seattle was hit with an earthquake measuring 6.8 in 2001, the damage was much less severe because it happened 60 kilometres below ground.

It also helped that many of Seattle’s buildings are constructed with features that make them better able to withstand the shaking and twisting that accompanies a quake.

Caribbean earthquakes

Jan. 12, 2010: Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Magnitude: 7. Widespread damage as epicentre of quake was 15 kilometres outside the capital. Number of dead unknown.

Nov. 29, 2007: Martinique region, Windward Islands. Magnitude: 7.4. Quake destroyed buildings, and much of the island lost electricity. One person died.

Oct. 8, 1974: Leeward Islands. Magnitude: 7.5. Damage was minimal, and no one died because the epicentre was far enough from any inhabited island.

Aug. 4, 1946: Samana, Dominican Republic. Magnitude: 8.1. Quake and resulting tsunami killed 1,600

Oct. 11, 1918: Northwestern Mona Passage, Puerto Rico. Magnitude: 7.5. Quake killed 116 people and caused $4 million in property damage.

Feb. 8, 1843: Leeward Islands. Magnitude: 8.5. At least 5,000 people died in a quake felt from St. Kitts to Dominica. This was the largest earthquake to hit the eastern Caribbean. In Antigua, the English Harbour sank.

May 2, 1787: Puerto Rico. Magnitude: 8. Possibly the strongest earthquake to hit the region. It caused widespread damage across Puerto Rico.

June 7, 1692: Port Royal, Jamaica. Magnitude: unknown. Quake killed 2,000 people. Much of the city slipped into the ocean.

On the other hand, most of Port-au-Prince’s two million people live in simple concrete buildings. It’s estimated tens of thousands of people lost their homes as buildings collapsed.

According to media reports, even relatively wealthy neighbourhoods were devastated. An AP videographer saw a wrecked hospital in Petionville, a hillside district that is home to many diplomats and wealthy Haitians, as well as the poor.

Experts say damaged buildings that are still standing will be even more vulnerable in the days and weeks to come as aftershocks rock the region.

The island of Hispaniola, which Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic, sits on the Caribbean plate, sandwiched between a major fault line to the north and another to the south.

“Large earthquakes are not a surprise in this region,” says Cassidy.

The fault line running under Port-au-Prince is known as a strike slip fault, meaning tectonic plates move past each other horizontally. California’s San Andreas fault is another example.

It is difficult to predict what the effect of Tuesday’s earthquake will be on the rest of the fault line running below Port-au-Prince. Seismologists are still developing the expertise needed to make such predictions, says Cassidy.

“When a rupture occurs in one section, it can change the stress in other areas, but it’s not clear if that’s the case in the Caribbean,” he says.

The last major earthquake in the region happened in 1946 and was a magnitude 8.0. It triggered a tsunami and left 20,000 people homeless, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.